“What he has given to the theatre is immeasurable.”

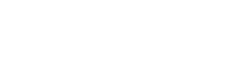

It was with these words that twenty years ago Harold Pinter referred to the great British playwright who is 80 years old tomorrow.

Born in Hampstead (London) on April 12, 1939, Ayckbourn began his career in the world of theatre at 17 when he started work as a stage assistant.

He owes first successes to Stephen Joseph, founder of Scarborough’s Library Theatre. Joseph became his mentor, guiding him not only in his work as stage director but also making an actor and a playwright of him. In 1958 Ayckbourn complained to Stephen about the roles he was playing, and Stephen answered that if he wanted better roles he would have to write them himself. Alan took him literally and wrote his first work, “The Square Cat,” which was a great success.

Since that day Ayckbourn has gone a long way and today he is considered one of the most prolific playwrights in the history of theatre. He has written over 80 works, including “Bedroom Farce,” “Family Circles,” “Absurd Person Singular,” “Confusions,” and his works have been translated in 35 languages and performed in theatres all over the world.

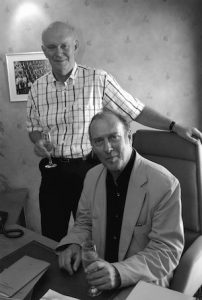

Ayckbourn, by his own admission, was influenced by numerous playwrights, from Chekhov to Coward, from Ionesco to Rattigan, but above all by Pinter whom he met in 1958 when Stephen Joseph invited Harold to direct “The Birthday Party”. Pinter chose Ayckbourn to play Stanley, the mysterious lodger staying at the seaside boarding house run by Mr and Mrs Bowles.

In an article published in “The Observer” on 6 March 1994, Ayckbourn remembers asking Pinter more information about the character he would be playing: “’Where does he come from? Where is he going to? What can you tell me about him that will give me more understanding?’ And Harold just said ‘Mind your own fucking business. Concentrate on what’s there.’

“… Pinter revolutionized the very nature of the play, Ayckbourn states in the article, “It’s very common to call him a poet, which tends to make him sound as if he writes everything in rhyming couplets, but he did use the play form and the play structure in a way that I don’t think people had done before. He says he owes a lot to Beckett, and I suppose that’s his nearest antecedent, but it’s a very different sort of Beckett. A very much more human face…”